western balkans

Where: Dubrovnik & Lokrum Island, Croatia. Sarajevo & Mostar, Bosnia Herzegovina. Podgorica, Scepan Polje & the South West, Montenegro. Pristina, Kosovo. Tirana & Durres, Albania. Skopje, FYRo Macedonia. Sofia & Buzludzha, Bulgaria. Europe.

When: July and August 2013

What: Sarajevo bomb roses, Sarajevo Twin Towers, Stari Most Bridge and Bosniak divers, Infamous Holiday Inn Hotel, Latin Bridge; assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Rafting down the Tara Canyon, Hoxha Pyramid, Tirana's Multicolour skyline, Nuclear bunkers, Pristina Library, Buzludzha UFO Communist HQ, Pristina Newborn Monument, Glavna Posta Building.

How: National Buses, International Buses, White-water Rafting, Walking, Taxi, Hostel Transfer Shuttle.

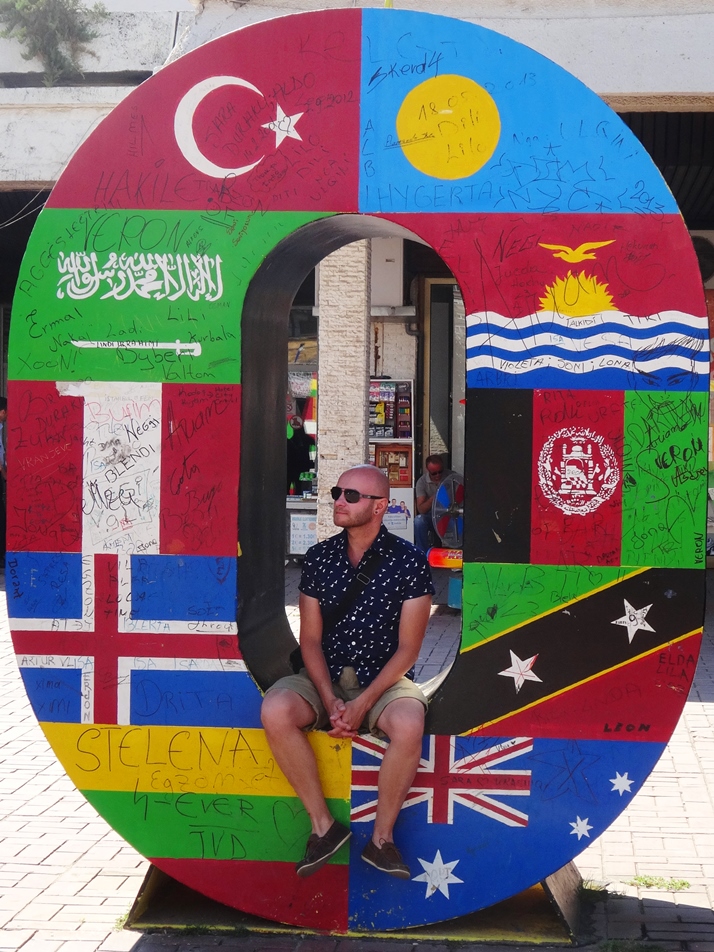

Country counter: No. 48 - 52.

Illnesses or mishaps: finding myself on a fast-moving raft in the Tara Canyon with a bunch of drunken Serbs; power cuts in Albania; sweating it out in several countries which were topping temperatures in the low-40s.

The Western Balkans region comprises some of Europe's newest countries. The fracturing of the former Yugoslavia into a series of increasingly smaller countries during the Balkans conflict of the early 1990s is testament to just how complex this sub-region of south west Europe is. The mixed international response to Kosovo's desire to become an independent country (recognised by the States and Britain, but not Russia), and Macedonia's full name still comprising the word "Yugoslav" with the bizarre prefix "The Former Yugoslav Republic of..." and often abbreviated to FYRoM underscores this region's embryonic and delicate nature and, as these two examples testify, it ain't over yet. After watching a five hour documentary on The Death of Yugoslavia I was only marginally enlightened as to the inter-woven ethnic, religious, cultural and political forces which served to fracture this region so absolutely. Iconic images from this terrible conflict include the Bosnian Serb bombing of the Mostar bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina, emaciated men being held in concentration camps, as well as Sarajevo's Twin Towers standing forlorn and battered by shelling - a symbol of a broken Bosnia. There isn't space to deal with the intricacies of the conflict here and I am not going to even try. Travelling around what constituted the former Yugoslavia is a chance to witness and experience a region in transition, a region still coming to terms with itself and a region, in many cases, only just beginning to glimpse tentatively in to the future.

Trains are something of a novelty in the Balkans: their frequency and reach are extremely limited. To the ignorant eye one would put this down to lack of infrastructure. When, however, visiting the countries themselves, one quickly spots the reason why: the mountains are huge and supernumerary. Thus, the only practicable and inexpensive way of getting from country to country is to do like the locals and get the bus, or coach, or minibus for that matter - for they come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. These services are run by small independent outfits or individuals, not large companies. Sometimes, therefore, you have no idea what the buses will be like or what their way of operating will be until you board. On some the air-con does not work, some are clean, others stink. Some drivers are helpful, others rude. Some charge to put your rucksacks in the hold, others do not. Many are driven well, some are not! One anachronistic aspect of these bus journeys is the fact that bus tickets are sometimes written out by hand. One thing is guaranteed: all of the journeys are interesting. If the scenery doesn't interest you, then the tense moments going through the borders will.

It goes without saying that a trip like this with so many countries involved is complicated. I am glad to say that the itinerary I put together (hardly backpacker style I know, but a degree of planning was needed if we were to manage all seven countries) barely changed and ran like clockwork - with just a couple of tweaks: what we'd planned, where and when is what generally happened. All in all the journey computes like this: 7 countries, 11 border crossings, 9 passport stamps, 3 tour guides, a massive 27 hours spent on buses transiting between countries, 2 time zones, 2 different alphabets (Latin and Cyrillic), 1 rafting adventure and over 1500 photographs taken. The number of kilometres we walked are inestimable.

The best part of this journey was the fact that it renewed and refreshed every time we headed off to our next destination - there was no chance of getting fed-up or jaundiced on this trip. Crossing countries one after the other in this way also allows you to tease out the cultural differences and similarities much more so than if you'd visited these places separately and at different times. Whilst some may consider The Balkans as one homogeneous geographical block, the atmosphere, levels of friendliness, religion, language, cuisine and politics are all of noticeably different hues. Admittedly, travelling like this was exhausting but travelling by bus did mean that we saw the landscape and country we were travelling through, something which is always forfeited when flying from country to country. Some bus times involved obscenely early starts, the heat in many of the countries topped 40 or 41 degrees - oppressive temperatures which served to sap our energy and curtail the time we'd earmarked for sight-seeing. In one country I could quite easily have cooked our dinner on the pavement. It was a good job, then, that people in the Balkans love their coffee! Like Balkan petrol, coffee stops kept us motoring onward. And boy, we needed the fuel as you'll see...

croatia

The Gem of the Adriatic

I'd been to Croatia before back in 2007 on the Inter-rail tour of twelve countries. Back then Zagreb, Split and some neighbouring islands offered us some welcome relief from the austerity of places like Serbia and Slovakia. This was my second time in the Adriatic country - and just like the first it didn't disappoint. I don't normally double up countries in this way, especially when there are so many I haven't been anywhere near but flying to Dubrovnik afforded us cheap access to the Balkan region. Croatia has embraced life after Yugoslavia far more than others. Its large stretches of Adriatic coastline and historical sights mean it has garnered the tourism pound more successfully than the rest. The Croats have well and truly left communism behind. So, Croatia Part Two it was with a very easy, and perfectly- civilised, stint in the famous walled city of Dubrovnik - and the start of our Western Balkans adventure.

dubrovnik & lokrum island

The walled red city of Dubrovnik is small and perfectly formed: its red tiled rooftops spread to the very edges of its ancient walls as if they were stopped dead in their tracks and prevented from spreading any further. As far as fortress cities go, it is rather impressive. It is a UNESCO Heritage site too - its steep lanes, shiny marble pavements and ancient archways making it a simple, beautiful and easy place to be a visitor. Little washing lines with linen and smalls dangle across from window to window, huge plants and trees spiral up in to the skies from amazingly-petite pots in lanes and, at every turn and in every crevice, there is a friendly café or restaurant to rest your feet. Expect to hear accents and tongues from across the globe in this miniature, Lilliputian place. It has the walled city feel of Malta's Mdina, the domes and clock towers of Venice and a well-organised tourist economy as good as any in western Europe. Expect prices to match western European ones too. The searing heat in July, however, is truly oppressive, with the marble pavements acting like a large mirror reflecting the sun's rays back up at you. Dive in to one of the side streets and chill out in an air conditioned café - before walking up the steep hill steps to sleep off the sun back in your rented room.

You can easily spend two days or two weeks in Dubrovnik. Indeed, if you want to sunbathe and take it easy along some of the most stunning coastline in existence then this is the place. For me, two days was enough; I am hardly going to see the world sat on a beach. So, with a ride to the top of the steep mountain on the Dubrovnik cable car, a three kilometre walk around the city's ancient walls at sunset, an iced coffee or two at the Buza bar "with the most beautiful view" of the Adriatic, plus a ferry trip out to Lokrum island with a little sweltering exploration thrown in, we were done and ready to move on. Booking our tickets the day before to guarantee a seat, we headed out by bus to Mostar, home to the famous stone bridge and made tragically iconic by news footage of its destruction by Bosnian Serbs in the war of the early nineties. As we did so we ploughed head first into our second country of the journey: Bosnia and Herzegovina...

The view of Dubrovnik and out to Lokrum island as seen from its city walls. Punctuating the uniformity of the red rooftops are a series of church domes and spires. From left to right these are: Church of Dubrovnik, SV Vlaho Church and Assumption Cathedral.

Technicolour kayaks on Lokrum Island.

Dubrovnik city view out towards the mountains.

City wall limits.

bosnia & herzegovina

The War-torn Country Embracing the Future

We entered into Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Croatian border through a seemingly endless series of border checkpoints. On our journey to Mostar we had our passports checked at three separate intervals by guards who boarded the coach with hand-guns in tow. To be honest, what I thought was stunningly beautiful Bosnian countryside could have been Croatian - with three border checks I was becoming a little confused as to exactly which country I was in. The third checkpoint was rather different to the previous two - which had been straightforward, simple tick-box affairs. On the third stop a guard boarded, checked passports in the expected way, and left. But then a second guard, dressed in different uniform from the first (and far less welcoming than the first), came in and took our passports - a scary moment for any traveller. The agonising wait started - I do not like letting my passport out of my sight but had no option. Bosnia and Herzegovina is, I was later to discover, chopped into two entities - a result of the peace deal between Serbia and Bosnia in the mid 1990s: The Federation of Bosnia & Herzegovina in the centre of the country and the Serb-dominated Republica Srpska in the north and south. It was, I suspect, our entry into the Srpska region where we experienced a frostier reception from authorities. With passports returned to us by a now weary driver, we zoomed onwards and out of the unnerving border politics and into a land of mosque minarets, roadside fruit stalls, three presidents, squat toilets and the incomprehensibility of the Cyrillic alphabet...

Indeed, signs of simmering tensions ooze out along linguistic lines here - dual language road signs which use both Latin and Cyrillic alphabets are defaced. Cyrillic is spray painted over or scratched off., for 'Cyrillic' read Serbian and thus Yugoslavia and thus former oppressors. The complexity of the country is captured in a number of curious facts, too. As mentioned previously, Bosnia and Herzegovina has three presidents, one for each of the main populations in the country once at war: Bosniaks (Muslim), Bosnian Serbs (Orthodox) and Bosnian Croats (Catholic). Secondly, Bosnia and Herzegovina is made up of three religio-political blocks; the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brcko, and the Republic of Srpska. Furthermore, Bosnia and Herzegovina has two separate police forces and two sets of laws as well as two central bus stations. Crossing from Federation to Republic is like entering a different country. There are no official signs to delineate the change, but you know: street signs turn from Latin to Cyrillic, drivers put on their seat belts and tell you to do the same, the people switch from open warmth to unhelpfulness, and the place looks more downtrodden and uncared for.

Bosnia & Herzegovina is a complex and scarred country but one I absolutely adored. She looked after us with warmth, great food and an astonishingly beautiful landscape. Thank you Bosnia and Herzegovina- we'd love to visit you again some day?

mostar

We arrived into Mostar's main bus station - a drab concrete affair which came with a side dish of unsolicited offers for "accomodations" from bus station hawkers. This less-than enticing introduction to Bosnia and Herzegovina quickly evaporated. The reception from hotel staff was the warmest and most genuine I have ever experienced and our waiter's sense of humour (shoving a whole ice bucket full of sugar sachets at me when I asked for one and shouting "take them all!") served to prove that you should never judge a place before you've experienced. Mostar was extremely pretty: sights and people. We took in the beautiful Mostar skyline with the rapid green waters of the Neretva River and the iconic Stari Most bridge from the top of the minaret of the nearby Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque (one of the few to survive unscathed from the war).

The bridge itself is a crucial symbol in a country of differing ethnic groups: it connects the predominantly Christian west bank with the predominantly Muslim east bank. It is, therefore, a physical bridge as well as a metaphorical bridge. The bridge symbolises the unity of Bosnian peoples and, in this context, its destruction in 1993 by Bosnian Croats was even more appalling. We visited Mostar on the unsettling twentieth anniversary of its destruction; twenty years on from when it tumbled into the raging waters of the Neretva below. We saw the obligatory Bosnian Muslim (called Bosniaks) diving from the bridge, too - a right of passage for young Muslim men. The divers work in small groups, collecting money in a hat before they dive for the hordes of tourists looking on with their cameras patiently poised. The divers have an agreement: they will not dive until they have reached a certain price in the hat. On one occasion, Igor, a sylph-like Bosnian Muslim diver, gave back the money collected from tourists as the price had not been reached and he could not, therefore, dive. I told him to keep it - but he insisted, shoving seven Kuna (the Croatian currency) directly back into my pocket. I have never been in a country where people give back their tips! And this tale alludes to another idiosyncrasy of Bosnia & Herzegovina - you can pay in any of three currencies (or a mixture of all three): the Euro, the Kuna and the Bosnian Mark. Waiters and shopkeepers are skilled at the conversions - and they didn't rip us off either. The prices we paid in Kuna, Marks or Euros were all fair conversions.

In sweltering temperatures we sauntered along the Turkish bazaar area, crammed to the rafters with some of the best crafts I have ever seen and umpteen cafes selling gorgeous coffee for 80p a go - so I had two rather than just one cup and polished them off with some Bosnian Baclava - something I have not eaten since my trip to Turkey. The Turkish culture is everywhere - Ottoman Turk roots run deep here hence the mosques, Turkish tea and the call to prayer echoing around Mostar's magical mountainous slopes. Mostar should be experienced by anyone visiting Bosnia Herzegovina.

The Stari Most bridge, rebuilt after being blown apart by Bosnian Croats in the war of the 1990s.

The Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque on the banks of the Nretva River.

Mostar's stone buildings survived the war.

A man plays the Baglama in the Kujundziluk bazaar.

Mostar's Kujundziluk Turkish bazaar: Ottoman-inspired cloth designs.

sarajevo

The road to Sarajevo took us through some of the most magical and spectacular landscape I have ever seen. Jagged grey mountains drop down into vividly rich blue waters, the road clings to cliff edges and occasionally cuts through the mountains themselves. The journey was punctuated by the regular sight of roadside honey sellers with jars of differing orange hues stacked in creative formations, an obligatory Balkan cigarette stop and a traditional Bosnian soundtrack playing on the coach radio. The journey to Sarajevo is a destination in itself - fall asleep on the coach and miss the lot. Like Mostar before it, Sarajevo was warm, welcoming and keen to share itself and its story. Scars are all around but the healing process is well and truly underway.

Sarajevo makes a very poor first impression - decaying concrete buildings are all too pervasive. The bus station is as dismal as it is run down but it's just a stone's throw from the capital's newest building the Avaz Tower. This was where we headed first. On floor 35 we took in the Sarajevo skyline along with a coffee. Annoyingly, the glass windows were tinted blue and so my photographs of Sarajevo from this upward excursion are blue in hue. Just across from Avaz is the infamous Holiday Inn Hotel - a mustard custard cube of a building which, during the siege of Sarajevo, was the only hotel left operating and was home to scores of international journalists reporting the war from its basement, including CNN and the BBC. Indeed, it is still perfectly easy to see the bullet holes in the hotel's outer walls, left as a reminder of the pivotal role this hotel played in bringing the siege to the world. Further down the road are the Sarajevo Twin Towers, the iconic buildings which were blitzed and bombed by snipers in siege news footage. They quickly became the emblem of a devastated, emasculated city under siege. They have now been fully restored in gleaming glass and arguably emblematic of a country's determined tenacity and resilience. Spots in Sarajevo where enemy shells landed are preserved with red paint on the pavement in around the city, dubbed "Sarajevo Roses". They are slowly but surely vanishing as areas of the city are renovated and resurfaced. However, I was able to see two which are preserved outside the city's Catholic Cathedral.

Sarajevo's Bascarsija district is a beautiful spot with its little cobbled streets and small independent shops selling anything from coffee to Ottoman-influenced trinkets. Its cosy single storey bazaar shops are punctuated by mosque minarets and pigeon feeders. Just a short walk from Bascarsija is the famous Latin Bridge, the site where Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austro-Hungary, was assassinated. His death ultimately sparked World War I. Unfortunately for me, the this most famous of bridges was irritatingly obscured by scaffolding undergoing, as it was, significant renovation. Our second day was taken up with the War Tour. Our Bosniak guide was keen to tell us, in the best English he could muster, the story of Sarajevo and the Serbian troops who encircled the city on three sides. Buildings all over the city are scarred with pop marks from bullets and blast holes from mortar fire; seemingly no building was immune. We explored under Sarajevo too - going into a preserved part of the Tunnel of Life - a lifeline dug by the Bosnian Army to help carry food and aid supplies to the trapped people of Sarajevo from under the UN-controlled airport. This tunnel kept people alive and gave Sarajevans a fighting chance - quite literally, as makeshift weaponry was also transported through here.

The wooden fountain and pigeons in the Bascarsija area of the city.

Sarajevo's in/famous Holiday Inn Hotel which, during the siege of Sarajevo, was the only hotel left operating. It was home to CNN and the BBC which broadcast war coverage from its basement. The outer walls are peppered with bullet holes.

In front of Sarajevo's iconic, and newlyrestored, twin towers.

A church squeezes between buildings in central Sarajevo.

montenegro

The Balkan Micronation

To travel to Montenegro you need to depart from the Republik of Srpska's bus station half an hour's drive from the cosy centre of Sarajevo. The job of the little woman in the ticket booth is to try to not sell you a ticket and to be as unhelpful and uncommunicative as possible. I have written about these characters before - they are a separate species found only in sticker-encrusted glass booths all over former communist countries, a sub-species born out of a communist mindset of "get what you are given". Lucky for us our guide from the War Tour did all the talking and we got our tickets to the Montenegrin capital Podgorica. Our Bosniak helper disarmed the woman's modus operandi - the pretend language barrier. Her main weapon is the Cyrillic alphabet and be warned: she eats tourists like you for breakfast. She had nowhere to hide when spoken to in the local tongue and so begrudgingly and sneeringly coughed up the tickets for the seven hour bus journey at a cost of 36 Bosnian Marks (15 Euros).

The journey is not one you can read or sleep through; the roads are bumpy and feature sharp bends as the road snakes around the mountains. The journey's highlights included the odd farmer holding up the bus with his staff to allow his cows to cross the road, a few crazy drivers in their clapped-out Ladas, and some achingly close moments as two lanes of vehicles negotiated single lane winding mountain roads with sheer drops below. I don't mind saying I was terrified on several occasions, resorting to gripping my chair and muttering expletives under my breath. Indeed, we were barely a centimetre from the cliff edge at one point. I'm not being dramatic, here, either: buses travelling around Montenegro are renowned for falling from cliffs and into the steep valleys below. Indeed, exactly this happened in June this year: the bus was full of Romanian tourists and there were no survivors. Making it to the border of the Srpska Republic and Montenegro, a Srpska policeman, fuelled by bravado and a lust for power, boarded our little bus and collected in our passports before swaggering off Into his immense power base - a white portacabin paid for by the UN. Luckily for us we became friendly with two Canadians from Vancouver and, at every pit-stop on the journey, reconvened to swap travel stories whilst all of the other passengers, Balkanites, puffed away on their cigarettes. Expect lots of breaks on journeys like these - Balkanites love their nicotine and, despite EU bans having been adopted in many countries, they are not really enforced. You'd better get used to the smell of smoke wafting up your nostrils.

Some curious facts about this tiny country: the name "Montenegro" translates as "Black mountain" owing to the black bark of a species of tree known to characterise the region. Montenegro is not in the EU but is allowed by the Union to use the Euro currency because it has a stabilising influence on the country. Montenegro also clung on to a Yugoslav-style partnership with Serbia as late as 2006 when the country finally became independent from Serbia - years after all other countries, lead by Croatia and Slovenia, had confined Yugoslav communism to the dustbin of history. Finally, Montenegro has recently added two new letters to its language, which is basically Serbian with a few dialectical differences. Perhaps this fact testifies, more than others, just how much Montenegrins want to move away from their old communist past by trying to differentiate itself linguistically from its old leaders in Belgrade. The language has been renamed Montenegrin in a bold linguistic re-branding exercise. Serbia, believed by many to shoulder more of the blame for the conflict than others (as the country which was home to the capital of Yugoslavia - Belgrade - it had most to lose) has been well and truly abandoned. Whilst there were atrocities on all sides, it was Milosovic of Serbia who stoked the fires of ethnic tensions to aid his own political ascendancy. Whilst no country came out of the war completely absolved of any blame, Serbia is perhaps more responsible than most.

podgorica

Heard of it before? Me neither. Heard of Titograd, then? This was Podgorica's name until 1992 under Yugoslavia - named after President Tito (Titograd literally translates as "Tito City"). Podgorica is in no way an internationally renowned capital city - so you'd better adjust your expectations accordingly (and do so in a downward direction). Podgorica is one of Europe's least-visited capital cities - and it is its hottest capital too. Podgorica is not going to win any beauty contests any time soon - but is well on course to win the ugliest city award. Its decaying concrete apartment blocks are as depressing as they are ubiquitous. Podgorica feels like an old Soviet frontier town - an outpost of the former Yugoslavia. For many years this is exactly what is was. It is stunningly ugly. And deserted. It was Friday night and we were the only ones in the restaurant. Many Podgoricans flock to the coast in the summer months to escape the city's fry-an-egg-on-the-pavement heat: only the lonely, the poor, the dispossessed or those that have to stay and work, are left behind. Government buildings are anonymous, white apartment block affairs - their national significance marked only by a pair of forlorn Montenegrin flags with faded colour. The city's TV centre would be indistinguishable from all of the other government administrative buildings were it not for its rooftop neon sign. Unfortunately, and all too characteristically, it only spells out "V Centar" as the "T" in "TV" has stopped working. The only photographic intrigue the city had to offer us was its white Millennium Bridge, which crosses the increasingly shallow Moraca River and soars like a newly-born dove into the Podgorican skyline. Only thing is, I think this dove is trying to escape the city as well. Like many a Podgorican and tourist before us we hatched a plan to escape, hiring a driver for the day from Montenegro Adventures, to visit the more photogenic sights crammed into the south western corner of Montenegro.

This cost was not budgeted for and was not money we'd planned to spend. However, I would have paid double to get out of the the city. A bail out? I don't think so. The Montenegrin capital is essentially a governmental and administrative centre and not its cultural heart. It does not, and therefore chooses not, to turn itself into a tourist-targeted theme park as is increasingly the strategy in larger capitals. Thus, acknowledging that we had made a slight itinerary error, we did what every self-respecting tourist would do in this situation: we threw money at it. I would have loved to have taken a local train out somewhere independently in true Bohemian style but the heat was just too oppressive. The Montenegrin weather does not lend itself so readily to sightseeing, only sleeping in darkened rooms with the air-con on full power. Enter, stage right, our driver Zoran, gateway to the Montenegrin South West...

The Podgorican skyline. And it doesn't get any better than this, I'm afraid. To the right is the TV Centre, although it is indistinguishable from the apartment block next door. Podgorica: I'm a traveller, get me out of here!

Welcome to Podgorica: atmospheric apartment letter boxes hark back to another age.

Podgorica street scene at sunset. I suspect all of the cars in this photograph are leaving.

Podgorica's Millennium Bridge.

budvar, cetinje, perast, kotor, sveti stefan & skadar

Montenegro's more photogenic sights in the south western corner include the former capital Cetinje with its fetching orthodox monastery, Kotor, a moated wall town reminiscent of Dubrovnik, Perast, a quaint village along the bay of Kotor with baroque palaces and island churches, and the spectacular scenery on the very winding mountain road out of Cetinje - detailed as a destination in itself by our Lonely Planet Guide to Montenegro. We bumped into our Canadian friends again and chatted for half an hour or so under the shade of a palm tree (topic: Podgorica), before heading back to Zoran's tour mobile to enjoy views of Budva and Sveti Stefan. We concluded the journey at Lake Skadar - the Balkans' largest lake shared between Montenegro and Albania.

The awesome view down to Kotor Bay from the Kotor to Lovcen mountain road.

The beautiful bay of Perast, a quiet Adriatic town, with the bell tower eclipsed by the huge mountain ranges.

The coastal town of Budva as seen from above - a smaller version of Croatia's Dubrovnik.

scepan polje

Our last day in Montenegro saw us travel back up north to the Bosnian border to do what many do when in this country: rafting along the awesome Tara Canyon. We left early to make it back up north in time for the big rafting adventure. I'd heard that Tara is deeper than the Grand Canyon in the United States but did not believe it. On seeing the canyon when we first entered Montenegro, I was left thinking that there was a fair chance that it was true! In fact, it's the second deepest canyon in the world. With almost no instruction, and with complete disorganisation, we were piled onto our raft - and set off tentatively perched on the side of the raft's inflatable sides, hooking our feet in the elastic cables on the raft's base. A couple of times, hitting the rapids, I thought we were going in - there was so much water flying about. I am not known for my "whooping", however the rapids were truly exhilarating and even had me "whooping" uncontrollably. These crazy rapid episodes were interspersed with long periods of drifting lazily down the canyon in the sun, the others sharing cigarettes and cans of lager which we were also offered. There were eleven of us on the raft - two Americans, us, and the rest were Serbian - all very friendly enough despite the language barrier. Two girls were particularly funny, perched on the raft's back with a cigarette and can of beer in each hand, not doing any rowing and shouting in English "Row, come on muscles!" They also translated the instructions from our Serbian lead rafter, who had taken to laughing and drinking beer like a duck to water. How these girls held on I have no idea and I forgave their laziness because they were completely hilarious.

We were collected from Podgorica at 7am, exiting Montenegro and back into Bosnia to start at the rafting camp. We were then whisked along toe-curlingly dangerous roads in an open-door minibus back into Montenegro to the spot where we'd launch the raft into the Tara. We rafted 25 kilometres of stunning Tara Canyon, and re-entered Bosnia Herzegovina yet again as we did so - passing the UN checkpoint up on the mountain road above. I thought I'd only be going to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro once. Technically I went to both three times! I can also, quite legitimately, claim that I have been white water rafting in both countries. The food back at Tara Camp in Montenegro was hearty and home-made - all cooked fresh and a vegetarian dish was made especially for us with no quibble. It was a long, sweaty journey back to the capital Podgorica where we had a bed reserved at the Montenegro Hostel - slap bang in the middle of a run down housing estate encrusted with political graffiti declaring "Kosovo je Srbija" (Kosovo is Serbian). The only reason we stayed here was because it would then allow us to use the hostel's transfer bus into Tirana, Albania - a snip at €35 each. There are no public trains or buses from Montenegro into Albania so this was our only option. The hostel was run by a lovely woman called Maya who did all she could to help and spent the time laughing and joking with us about Montenegrin and British habits ("oh, of course you are British - I like you as you are black and white, you say yes or no. In Montenegro they don't commit" and "Montenegro time is always later than planned - we are always late...") I tried to be polite by stating that Podgorica was "interesting" even though there was not much to do. Her response was "no it's not - and I was born there". She was memorable because she was honest, intelligent, ballsy and fun and I liked her a lot: a real character which you are blessed to come across, if you're lucky, on such a trip as this.

Preparing to raft through Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro.

The stunning Tara Canyon with its turquoise clear waters, lush greens and moody greys.

On-board the yellow raft (I am bottom, right) as shot from a photographer on a canyon slope. Clearly I was the only one on the raft who had no idea we were being photographed.

Hitting the Tara Canyon rapids.

albania

The Reclusive Country Opening Up to the World

The three hour journey from Podgorica in Montenegro to the Albanian capital Tirana was memorable because of the 40 degree heat (I had sweat running down my legs - I never knew my legs could sweat!) and the fact that our van's air conditioning had failed - along with the front right tyre too. The driver had to keep stopping at petrol stations to re-inflate the damn thing. Another set of passport stamps as we exited one country and entered into another. Albania was our fourth country of the journey and my 49th overall.

Albania has, for decades, been an isolated country. It was not part of either the Soviet Union nor the Yugoslavia Federation controlled from Belgrade. It was a paranoid communist country ruled with an iron grip by its leader Enver Hoxha who ordered the buildings of hundreds of thousands of concrete bunkers all over Albania. Indeed, we saw three of these on entering Albania at the Montenegro border. Spookily they leer at you from among the bushes and rocks like concrete voyeuristic toads squatting in the landscape. The overwhelming feeling when you see one is that you are being watched through the rectangular slot at the front, hence why so many have now been destroyed in the new modern Albania. Albanians were not allowed to travel outside of their own country until 1991, consequently enveloping the country in mystery and secrecy which has not exactly endeared it to outsiders.

The road to Tirana is an enjoyable one to journey through. Farmers sit aloft their horse drawn carts, shacks made of leaves sell an incalculable number of green melons, and the road is littered with independent cafés and gaudy restaurants with ironic names like "Palace Restaurant". This is clearly not a country without money, although that is not to say that you won't see poverty on your journey, often involving Roma gypsies and their children. Expect, then, babies to be dangled by their mothers in to the windows of moving cars in the middle of crazy roads, expect the old trick of windscreen washing whilst you are stationery at traffic lights, and expect to see people of no fixed abode asleep in parks. One Tirana waiter explained to us that Albania's boom was down to money pouring in from the Middle East (Qatar) as well as the laundering of drug money through the building industry.

Albania, like many a former communist country before her, sees her future within the EU. Indeed, EU flags presumptuously partner red Albanian ones across the land. It is clear that the EU as a geo-political force is motivating governments across the poorer parts of the continent to accelerate improvements in infrastructure and democracy. Some would argue that not all Albanians are benefiting from this Albanian boom. The people are perfectly friendly and, confusingly for us, like Bulgarians, they shake (in wobbly fashion) their heads to mean yes rather than no. This had us confused and amused in equal measure on a few occasions. It is fair to say that Albania does not have a good reputation abroad - I was, however, pleasantly surprised - and not for the first time on this journey. I love it when this happens in travel: all of your preconceptions melt away. I was expecting aggressive beggars, crazy drivers, power cuts and dilapidation. What we got instead was a friendly, colourful country with all the modern conveniences a traveller could ask for (and proper coffee too!) Admittedly I was right about the power cuts.

tirana

We arrived into Tirana at the city's Skanderbeg Square - instantly it was clear that the whole square has been redeveloped since Michael Palin had filmed there for his New Europe series in 2007. The white communist era National Palace of Culture and Opera buildings now sit in a well-landscaped square (rather than on the edges of a crazy roundabout) with trees and grass, several gigantic Albania flags waving in the breeze, and the equestrian statue of Skanderbeg himself (the statue of Hoxha was pulled down in 1991) centre stage.

Having dropped off backpacks at the hotel, a stone throw from Skanderbeg, we headed to the Sky Tower hotel's rooftop restaurant which, after feeling dizzy and disorientated whilst drinking my coffee, I realised was actually rotating and the skyline with it. Seeing Tirana from above allowed us to enjoy the extent of the Mayor's plan to brighten up the city by painting communist tenements in a range of colours and patterns. The Mayor, Edi Rama, now the Albanian Prime Minister, is an artist. From such a high vantage point Tirana appears as a rainbow, technicolour city.

Whilst the turning of Tirana into an artist's canvas points to the future, relics of the country's dark past continue to spoil the party. Two bronze statues, one of Lenin and one of Stalin, have been hidden behind the National Art Gallery. They are accompanied, in a sort of police line-up of rejects, by three other socialist realist statues from the Hoxha era, as well as an abandoned car with its windscreen smashed in (see here). Dramatically the statues of Lenin and Stalin are shrouded in plastic sheets. At first I was annoyed at this because it meant that I could not photograph them. However, on reflection, I think this spectacle symbolises Albania's journey from communism to capitalism perfectly in a single image. Perhaps, and tritely, the abandoned car alongside symbolises the fact that, for many Albanians at least, communism's dark era has reached the end of the road; the plastic sheeting, held down tightly with straps; communism's final humiliation.

Tirana skyline . Colourful apartment blocks of Tirana as seen from the Sky Tower hotel's rooftop cafe. The Mayor's plan to brighten up the capital was to turn Tirana into an open-air art gallery. I'd say he's partially achieved his vision.

One of Tirana's architectural hangovers from the communist era; the huge Hoxha Pyramid, a museum built in the 1980s but which, after the fall of communism, became a concert hall and then, humiliatingly, a disco.

The immense The Albanians mosaic mural which adorns the front of the National History Museum in Tirana's Skanderbeg Square, depicting historical Albanian triumphs. After the fall of communism in Albania it had its communist star removed.

durres

Durres, until the 1920s, was Albania's capital. It is now a seaside city a convenient distance from Tirana. Among travellers it is well known as the place of Hoxha's seaside concrete bunkers. Short on time we hired a driver to take us there in the hope of catching some of the concrete mushrooms - many, I was aware, had been re-purposed into holiday huts, small kiosks. Sadly for us, but not for the Albanians, virtually all have been removed. It looked like we were on a fruitless mission. Conversations with people in hotel lobbies, the drawing of maps, phone calls back to our hotel to retrieve our driver from his coffee break, and another drive further south brought us to a stretch of beach frequented by Albanians enjoying the sun. We tracked down a larger bunker which had been transformed into a restaurant called "Bunker". It was, sadly, unrecognisable as a bunker and could have been any old eatery. Sweat running down our backs, we decided to at least walk a bit further down the beach before returning crestfallen. Then! Three! Three of them poked out from the ground in someone's back garden, her house backing, as it did, onto the beach we were walking along. We asked permission to take photographs and she was more than happy: one bunker in particular had become a convenient mount for her satellite dish. Our perseverance had paid off. These weren't the colourful ones I was hoping to see, but I was more than happy with what we'd found.

Sitting on top of one of the few remaining Hoxha bunkers, built by a paranoid communist country in fear of nuclear attack.

kosovo

Europe's Newest Country

Is Kosovo a country? Is it just a region of Serbia? Is it semi-autonomous? The States and the United Kingdom have accepted that Kosovo is its own country, and that Pristina is therefore its capital after it declared independence back in 2008. Kosovo is a complicated country populated mostly by Albanians but with a small Serbian population. In 1992 Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic attempted to purge the region of all Kosovar Albanians and refill it with Kosovo Serbs in a bid to reclaim the territory. Ethnic cleansing, in short. In 1999, after nearly 850,000 Kosovar Albanians had fled into neighbouring countries, some making it to the United Kingdom, NATO finally intervened and started bombing raids on Serbian troops, which then withdrew, leaving Kosovo a UN-NATO protectorate. Powers have since transferred from the UN to the Republic of Kosovo government, but Serbia is refusing to relinquish, entirely, its former heartland. The remaining Kosovo Serbs live in guarded areas of the country.

There were only two services per day from Tirana to the Kosovan capital Pristina - one at 6am, the other at 2pm. We opted for the early bus in a bid to avoid travelling in the worst of the heat. Luckily the bus stopped right outside our hotel. The bus service appears to be run entirely by a thin woman with a penchant for luminous clothing from her little travel agency just off of the main Skanderbeg Square. For €15 (the Euro is also the official Kosovo currency) you have the pleasure of sitting on a grubby coach with no air conditioning and Turkish-inspired music playing through the speakers...for six hours. Half-way through the journey, we pulled in what looked something like a border checkpoint and a thick-set policeman collected passports in the normal way. We then had to get off the coach to have our bags scanned. We left ours in the racks and so spent time chatting to a couple about our journey. I was not officially checked out of Albania but did get a stamp from the "Republic of Kosovo". Having this stamp in your passport is a sure-fire way of being refused entry into Serbia. If you're lucky they may permit you entry, but not before stamping over your Kosovo stamp with a Serbian one. Friendly. Kosovo was my 50th country.

pristina

Entry into Pristina, like many Balkan countries, takes place at a drab bus station. After getting a taxi with two German girls into the 'centar', and following a little altercation with the taxi driver involved, we headed into Kosovan life - set to be Europe's newest country. It becomes clear rather quickly that Kosovans aren't used to visitors. Expect lingering stares and second looks (even grins) from locals - all of which were a little unnerving to begin with. Pristina does not feel like a capital city, more a provincial town undergoing significant development. The map inside our Lonely Planet Guide to the Western Balkans, dated 2009, bore only a tiny resemblance to the city centre we now found ourselves walking through. Roads had changed, new fountains installed and a gleaming new Republic of Kosovo parliament building stood brashly at the end of Mother Theresa Boulevard. The rush has obviously been on to build a capital city worthy of the name - to upscale a previous Yugoslav market town into a capital city of Europe's youngest (and most controversial) country.

Controversy can be read in the ubiquitous presence of the EU, UN, NATO and USA flags which fly outside every Kosovo Republic building as if the flags themselves are shields of protection against any future aggression (politically or otherwise), a visual trumpeting that Kosovo has friends in high places. We saw a dozen UN trucks parked up in a Pristina yard, buildings being refurbished with financial help from the "US People", and the number of buildings in Pristina given over to EU personnel is quite remarkable for such a small city. Kosovo is a country in need of friends - and it appears they have them if these sights are anything to go by. Indeed, in central Pristina there is now a "Bill Clinton Boulevard" and even a "Tony Blair Street".

For the tourist in search of sights Pristina has limited offerings. Expecting grand sights kind of belies the whole point as there is only one main attraction that trumps anything you may see in other, more grander, capitals around the world: the chance to experience a much-reported and much-maligned place for yourself and to witness the growth of a new country first-hand. This is Kosovo's main attraction and it is one which is crystallised in its capital Pristina. Wars and communist-style town planning, plus an unregulated building frenzy since its declaration of independence, all mean that Pristina has lost many of its historic buildings. The National Library or Bibliothek is undoubtedly Pristina's most perplexing and original building. Built in 1982 when Kosovo was part of Yugoslavia, its carbuncular concrete blocks are imprisoned by large geometric metal cages and topped by a dozen or so white bulbous domes. The fact that it was built during the Yugoslav period adds to its grim potency. It is remarkable and, in my opinion, worth a visit to Kosovo just in itself. We even entered into Pristina's new university building opposite (without permission), as well as blagging a trip up to the actual roof of Pristina's tallest hotel, The Grand Hotel, on Pristina's main street to try to get a shot of it from a higher vantage point. They really didn't want to take us up there but I'd emailed ahead and hotel reception staff had no wriggle room; they reluctantly escorted us onto the roof. You don't ask, you don't get, right? Another architectural hangover from Pristina's Yugoslavia days is the now near-abandoned Palace of Sports and Culture which looks not unlike a spiky, upturned concrete insect dying on its back. Its beige legs can be seen as you visit the newest and most iconic addition to Pristina's must-see list. Th "NEWBORN" monument has giant 3D letters which mix political sentiments for autonomy with artistic creativity (the letters are re-themed every so often to fit in with other events in the city). It is the landmark most associated with Kosovo's new-found independence and is just as much an attraction for Kosovans as it is for foreign nationals.

Stay in Pristina one night - give it a chance and help the Kosovar economy at the same time. After getting over the initial shock of seeing you, an actual tourist, Kosovans will still look grumpy but this is just their reserve. Their stares are not meant to be threatening either but are borne out of sheer curiosity. As we were to find, people in Pristina are keen to help and engage with anyone who has taken the trouble to visit their emerging country. You will find a quiet, sleepy town which has the local population, rather than the tourist, in mind.

The Newborn monument. Giant 3D letters mix political sentiments for autonomy with artistic creativity. It is the landmark most associated with Kosovo's new-found independence.

In front of the Kosovo flag outside the Palace of Sports and Culture.

The Bibliothek building is Pristina's most original building, its carbuncular concrete blocks are imprisoned by large geometric metal cages and is topped by a dozen or so white bulbous domes.

fyro macedonia | north macedonia

The Former Yugoslav Republic

Pristina in Kosovo is perfectly placed for it to feature as a stop-over point for those wanting an onward journey to Skopje - the capital of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (in 2019 the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia was renamed North Macedonia). This was, indeed, the next stop on our Western Balkans journey, being only two hours away from Kosovo on the bus, with regular services daily. The name of the country remains prefixed with the words "the former Yugoslav Republic of" because there is already a place in Greece called Macedonia - and the Greeks are, perhaps understandably, unwilling to share the name. There is also a significant amount of historical bad blood between the two, so much so that Greece continues to block Macedonia's attempts to join the EU. The country, therefore, seems more unable than most to shake off the auspices of Yugoslavia.

Arguably, FYRoM's flag harks back to communist times with its yellow idealised sunrise motif on a bright red background. This may account for its low profile on the international, even European, stage - saying the word "Skopje" to most is unlikely to elicit a situation of knowing and familiarity in the listener, but more likely one of ignorance and puzzlement. This, however, does not mean you should not visit. Sometimes it is the quiet, unassuming countries which are the most surprising - and this has been the whole point of my Western Balkans journey: dispelling the myths, travelling off of the beaten track, and going to the places other travellers choose not to reach...

skopje

The first thing that you notice about Skopje are the bronze statues. There are hundreds of them. We arrived on Friday lunchtime and the only people to be seen were bronze ones. There were more statues than people. There is a reason for this proliferation of metal people: a massive commissioning of statuary by the Macedonian government and an attempt, undoubtedly, to re-forge a national identity after years in the wilderness and to simultaneously improve the appearance of the city following the terrible earthquake of 1963 which devastated the capital. There are statues from every chapter in the country's history. Controversially, some neighbouring countries are claiming that, in amongst this new statuary, are some of their national heroes too! This bronze population conjures up the scene from The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe where all of Narnia's people have been turned into stone. Add to this the absence of real people (it was a national holiday on the day we arrived) and you are left with a very unsettling feeling. The statuesque population is accompanied by new huge, gaudy fountains (one of which plays classical music), as well as new bridges spanning the Vardar River. Indeed, one in particular is cluttered with statues and lanterns. Twenty new buildings, including a new national theatre, concert halls, museums and administrative buildings have been thrown up in the last few years as part of this turbo-powered project, called "Skopje 2014", with many being built in a classical Greek designs with Corinthian columns. This is town planning on steroids: rather than looking grandiose and impressive, it all feels a little bit theme park. Skopje is coming dangerously close to being the subject of ridicule: my instant reaction on arrival in Skopje was one not of awe, but of laughter, so absurd did the city appear to me.

Skopje's Carsija district, the Turkish area complete with mosques and cobbled streets, offers you a city on a far more human and intimate scale - a nice break from all of the hyperbolic embellishment of the new Skopje. To really appreciate this part of Skopje, which oozes real history rather than a retrospectively manufactured one, treat yourself to a coffee at the top of Hotel Arka which overlooks Carsija's little red rooftops, bazaar area and half a dozen or so minarets. The views continue 360 degrees out towards Skopje's huge Millennium Cross perched on the peak of Mount Vodno, the black boxy bulk of Macedonia Television, the Kale Fortress and the fifteen grey-green domes of the Hamam (Turkish baths). Zoom in and you also get a bird's eye view of the Stone Bridge and the Macedonia Square it leads to. It's a pretty awesome spot from which to gather your bearings and appreciate the city in its totality.

Skopje has more than its fair share of communist era buildings principally because on the 1963 earthquake which spurred a massive building programme. The brutalist concrete Glavna Posta building, part of this programme and once prominent on the Skopje skyline, is now squashed in by more recent and far less unremarkable buildings. It's a bit of a shame, but you can still appreciate its geometric shapes and raw design. The old railway station is worth a trip too; its clock is evocatively stuck at 5:15pm - the time the 1963 earthquake hit. The building was mostly destroyed, but what remains has been secured and is a museum marking the moment in time Skopje changed forever. Other unusual sights include the St Clement Church of Ohrid - an interesting take on church architecture with its distinctive arched roof pulled down to the ground at various points. Also of interest is the statue of Mother Teresa which stands on one of the main shopping streets in the city - Macedonia's most famous gift and export to the world.

Skopje is a strange dish with a mixture of seemingly incompatible ingredients: Yugoslav communism, Ottoman influence, Orthodox religion, hilltop fortifications, some garishly kitsch town design and mainstream European culture - all stirred with a serious earthquake and baked at 40 degrees. A side order of irritating Roma Gypsies with their hands outstretched is not always optional. Skopje is a dish whose ingredients seem to complement each other - a concoction which surprises, delights and disgusts in equal measure; its recent steroid injection makes a veritable feast for your camera (I am aware that I'm now mixing my metaphors). Be sure to taste Skopje - it's only a matter of time before everyone elsewants a slice of this uniquely Macedonian dish - you may find it an acquired taste but isn't that the whole point of travel?

The unusual St Clement Church of Ohrid with its distinctive arched roof pulled down to the ground.

Brutalist Skopje: The Glavna Posta building, the black Lego-style blocks of the Macedonia Television building and an apartment building.

A city with grand designs: in front of Skopje's new Constitutional Court building along the river. To the right is one of the city's new stone bridges.

Skopje's Carsija district, the Turkish area complete with mosques and cobbled streets, offers you a city on a far more human and intimate scale seen from the Hotel Arka.

bulgaria

Eastern Balkans

I had been to Bulgaria once before visiting the capital Sofia and its second city Plovdiv. As explained earlier, Bulgaria is well connected with flights back to the United Kingdom so, when mapping out the Western Balkans adventure, Bulgaria was a cost-effective and logical end point. It would also give us the opportunity of rectifying a regretful omission from our last visit - a trip out to the Central Balkan Mountains to see the Buzludzha UFO. The road to Bulgaria from Macedonia was comfortable enough, catching the 8:30 service from the central bus station and travelling for five and a half hours with a longer than expected transit through the border. As we entered into Bulgarian territory we exited the Western Balkans and entered the Eastern Balkans.Indeed, its distance eastward means that local time is GMT+2 - so instead of arriving at 2:30pm, we arrived at 3:30pm Bulgarian time. Crossing the border also meant a dumping of the Macedonian Denar and saying hello to the Bulgarian Lev.

Bulgaria is at a crossroads. On arriving in the country, protests had reached their 52nd consecutive day against government policies which seem to be exacerbating inequality and the widening of the gap between rich and poor. It all sounds depressingly familiar. Key government buildings were being protected by the Policija in dark blue uniforms and their dark blue vans; a slightly ominous start, then, to the last country of our Western Balkans adventure.

sofia

Returning to Sofia felt like catching up with an old friend. Streets were familiar and, perhaps embarrassingly, we even ate at the same restaurant - and sat in the same place. Prices have noticeably increased since our last visit, however, the practice of taxi companies copying each others' logos has been stamped out and the dangerous Sofian pavement surfaces, with their pot holes and twisted metal skewers waiting to impale you, are being dealt with. Noticeable improvements, then, on the surface - literally and metaphorically. It seems that every capital city we've experienced on this journey is smartening up its act in a bid to guarantee itself a place at the EU dining table. Indeed, Sofia's main entertainment street, Vitosha Boulevard, with its bars, cafés and restaurants, was as lively as ever - the eateries themselves having also upped their game with newly-designed interiors and frontages. It was Jazz music playing now, not Europop. As this is my second visit to Sofia, I will not labour this section, only to say that I couldn't resist taking a few snaps of the capital's key landmarks for a second time with my new camera in a bid to better that which had gone before.

The Alexander Nevsky Cathedral - Bulgaria's most famous landmark with its Neo-Byzantine style and one of the largest eastern Orthodox cathedrals in the world.

Some of Sofia's geometric designs reminiscent of the style adopted by architects and street planners during the communist era.

The former Communist Party House, former headquarters of the Bulgarian Communists. Its red star has long been removed and replaced by the Bulgarian flag. The building's design imitates key characteristics of the Stalin Palace.

mount buzludzha

Buzludzha is some 250 kilometres south east of Sofia. Public transport does not lend itself to travelling to this place as so few people actually want to go here. It features only nominally in the Lonely Planet Rough Guide to Bulgaria - one paragraph, in fact. You could be forgiven for missing this destination out entirely because you didn't even know it existed. You won't find this building on any Bulgarian postcard or in any Bulgarian brochure. It is home to one of the most bizarre and curious sights ever built. Many Bulgarians despise it. The Prime Minister wants it demolished - if only they had the money to do so. It stands forlorn and abandoned high up on a hilltop, a cosmic, concrete externalisation of a failed socialist system which Bulgaria is keen to shuffle off into the vaults of time labelled "Forget". It is the Mount Buzludzha UFO building, a once grand concrete meeting place for communists. Politics aside, it is one of the most marvellous examples of cosmic communist architecture there is and acts, I believe, like a touchstone to the ideology and period which built it. For this reason alone it should be preserved. It is a little trite to say that the state of the building is a perfect metaphor for communism itself - but I suppose that's what it has become: like communism, the building was cheaply executed, illusory and full of obscene hyperbole and, ultimately, completely unsustainable. Marooned on a hilltop, and an uncomfortable relic reminiscent of a darker Bulgarian past, it has been handed over to the Socialist Party of Bulgaria - which has failed to do anything with it except lock its doors and leave it to rot. Except, as you'll see below, they even failed to secure the building fully. I managed to get inside.

However, more recently there has been a buzz on online discussion boards about this incredible place as more and more would-be explorers search for ever more strange and otherworldly sights. Buzludzha has also featured in the top ten travel photographs of 2013 polled by The Times newspaper in London. I arranged, through an international tour guide website, for a Bulgarian guide called Petar to drive us out to Buzludzha. Leaving at 9am we passed through golden Sunflower fields and impressive mountain ranges as we headed south eastward to one of Bulgaria's lesser-known, and more remote, sights. Advice on online travel forums told us to "take a torch". Indeed, as you approach the structure from the Shipka Pass, it is clear that the building, as a little taste of what's to come, has two immense torches of its own, sparkling in the sun. They greet you imposingly. Arriving at the mountaintop and beholding the soaring turret and extra-terrestrial UFO disk is a travel moment I will never forget. Walking around under the huge disk you are treated to wonderful 360 degree views of the lush, green mountains and a windfarm on the horizon. The Cyrillic lettering on either side of the main entrance translates as: "On your feet, despised comrades! On your feet you slaves of labour! Downtrodden and humiliated, stand up against the enemy!" I was keeping an eye out, all along the way, for the way in to the building which people had spoken of. Initially I couldn't find it and was convinced that it had been secured and concreted up. But there it was! Without hesitation, I scrambled up the stack of rocks which other visitors had piled under the opening to aid their own entrance, torch in tow, and dropped down into the building. This is quite clearly the weirdest thing I have ever done whilst travelling. If you are interested in this sort of thing it is an absolute must of a trip. It is weird, yes, but fascinating in equal measure. If you are not interested, and would prefer reviews of sunny beach resorts and package holidays to the sun...then you're in the wrong place.

Recording my entry on camera as I picked my way through the rubble, illuminated by the torch, I made it to the central auditorium - with a jaw-dropping 360 degree mosaic all around featuring communist motifs and symbols: clenched fists, red stars, unified groups of workers, geometric patterns and portraits of three communist visionaries Marx, Engels and Lenin. Artistically it is magnificent. Above my head was a huge hammer and sickle symbol on what was remaining of the ceiling, through which daylight was now streaming. To say it was an eerie experience is an understatement but I feel really, really lucky to have seen it; the condition it is in means that it is unlikely to last much longer. Buzludzha was an incredible end to the journey we started over a fortnight earlier on the safe, civilised Croatian coast. Coincidentally, on arriving back home in the United Kingdom, my copy of Lonely Planet Magazine was waiting for me on the doormat. As part of its 40th anniversary celebrations, it featured a trip to...Mount Buzludzha.

The incredible UFO-esque concrete communist headquarters on top the a mountain in the Central Balkans Mountain Range.

Left to right: evocative crumbling Cyrillic lettering; at the front entrance; entering through a small opening at the back of the building. In an old Bulgarian dialect the Cyrillic lettering says, "On your feet, despised comrades! On your feet you slaves of labour! Downtrodden and humiliated, stand up against the enemy!"

Stood in front of the huge torches.

The dramatic hammer and sickle detail of the auditorium ceiling.

A revolutionary mosaic murals collection with typical communist motifs like the red revolutionary star, images of unity and a mural of strength in unity and mosaics of Marx, Engels and Lenin.

Buzludzha from a distance.

The stunning view from the top of the Buzludzha monument across the Central Balkan mountain range. Wonderful.

travel tips, links & resources

- On a big trip involving many countries, try to purchase your next ticket on arrival. This means you don't have to head back to the station to buy any onward transport and can spend all the time you have enjoying yourself knowing your next journey is all arranged. Many of the countries I travelled to and through did not readily allow online ticket purchasing, meaning the only option was to pay in person at a ticket counter.

- Take any conversions and time changes with you so you know exactly where you stand when you arrive in a new land; particularly important if you have onward travel connections and you don't readily have roaming internet access.

- Bosnia is a very green country but don't get carried away with any romantic notions of going out walking in the hills; there are hundreds of thousands of unexploded mines left over from the war and their removal is a slow and painstaking process. If you do opt for the scenic route, stick to well-trodden paths.

- Without the help of the In Your Pocket guides, I would not have been able to work out the availability of buses in/out of countries. Whilst some are out of date, they pretty much give you an accurate sense of what bus-related transport you can expect in the Western Balkans. Remember: trains are few and far between - buses are the only realistic way to travel between countries in this part of Europe. You can access their website from here.

- The heat in many of the countries we visited topped 40 or 41 degrees - oppressive temperatures which served to sap our energy and curtail the time we'd earmarked for sight-seeing. If you can avoid travelling around the Balkans in the summer months, I would advise doing so.

you may also like